The patio of the castle of Vélez Blanco (Almería, Spain) has lived multiple lives. Its trajectory has been extraordinary: from the innovative, humanist surge toward new art and new ideas important in the patio’s conception in early 16th century Spain to an upheaval of monumental proportion culminating in its reconstitution in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art; from the generous expression of institutional, academic and historical responsibility fundamental to the patio's preservation and protection to the heroic leap of imagination and technology required in facilitating its upcoming re-creation. Running alongside this extraordinary trajectory is an utterly human, changeable story of shifting fortunes, loss and separation, craft, art, connoisseurship, humor, ambition and collaboration.

Having grown up in New York City, my own affection for and familiarity with the castle’s displaced core were already in place. I spent my childhood at the Met, wandering around the elegant Spanish courtyard, with its soaring ceiling and pale marble, with its cascading vines and strange beasts. My first experience with the Castle in Spain happened quite by chance in 2010, during a drawing residency at Joya: arte + ecología. I had traveled so far, deep into the beautiful province of Almería, Andalucía, only to find myself inside a room I knew so well. In retrospect, neither the castle in Spain, nor the patio in New York, ever felt to me to be missing anything. Both places seemed full of opportunity, ripe for further imaginative exploration.

The image of the two castles that began as one, doubled and split, has always struck me as a unique invitation to locate where the actual Art resides. If the marble decoration now at the Met represents the patio’s “skin", the public facade, the face that greets the guests, viewers, castle-goers and art-lovers - what is left behind after its removal? Without skin, does the empty courtyard represent the castle’s bones? Or was the courtyard stripped to its soul? Does the double trajectory of a divided self make more art and more history? Or does it create a lesser, diminished half-story? Is there any instance, version of history or self-reflection, in which “interior" and “exterior" line up, work together, move forward in concert? The contemporary fluidity which allows us to occupy both spaces with relative ease is new and generous. If the guests, viewers, castle-goers and art lovers show up in either of the two spaces, do they have a shot at meeting the castle’s soul? Are there now two different souls? One divided soul?

The patio carvings themselves are full of symmetry, doubling and imaginary hybrid creatures. It is the work of Italian craftsmen, carved from local marble, inspired by the rediscovered forms of antiquity. In my imagining, the castle and patio represent an action-packed, ricochet story: excavating the past in order to draw the future; connecting the dots between craft, material, art and context; forms derived from Nature provocatively intertwined with Humanist ideas about culture and progress.

Double Self Split color #4, 2015/2016, color pencil on paper, 17” x 69”

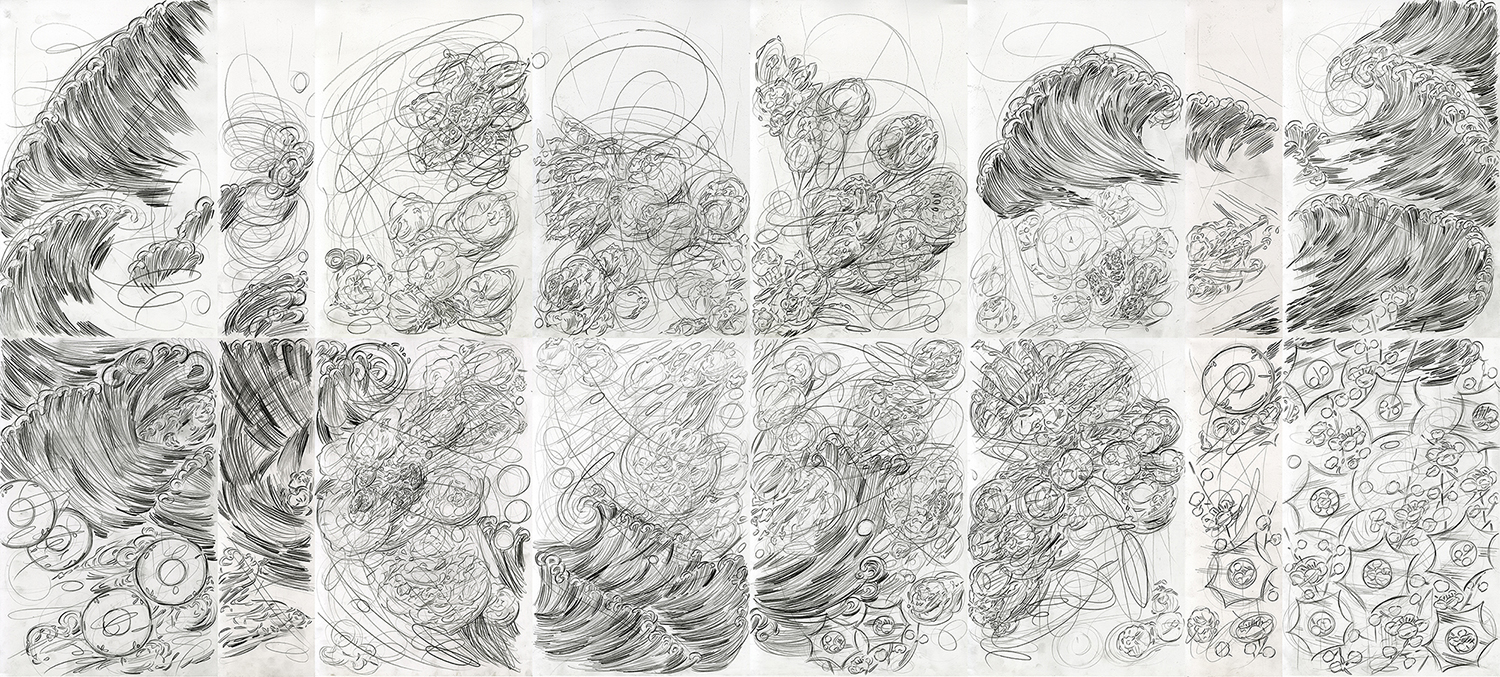

Double Self Split #3, 2015, pencil on paper, 17” x 69”

PROJECT

The trajectory of my own intersection with these incredible places and ideas is the result of an ongoing collaboration with the forward-thinking philosophy of Joya: arte + ecología. Their mission provides an open definition of a productive, sustainable ecosystem which includes research, restoration and conservation, science, technology and art in an attempt to establish a meaningful attachment to our societies and the environment. The corporeal roots of their project thrive thanks to their grounded commitment to the history, culture, economy and agricultural practices of their spectacular location in Almería, Spain.

Iglesia de San Luis

Iglesia de San Luis, Vélez Blanco.

The drawing exhibition inside the 16th century Iglesia de San Luis in Vélez Blanco will be comprised of sixteen large composite drawings, monochrome and color, housed in eight, double-faced, standing frames to be distributed across the nave and aisles of the church. The reappearance of drawings in Vélez Blanco references the dissemination of ideas, architectural forms and decorative motifs via prints and drawings as an influential practice throughout the Renaissance, across Italy and Spain. In a contemporary version of drafted information-sharing, new drawings, inspired by the patio’s history and design, will cross the Atlantic back to Spain, five hundred years after the patio was first conceived.

Castillo de Vélez Blanco

View of the Castillo de los Fajardo, Vélez Blanco.

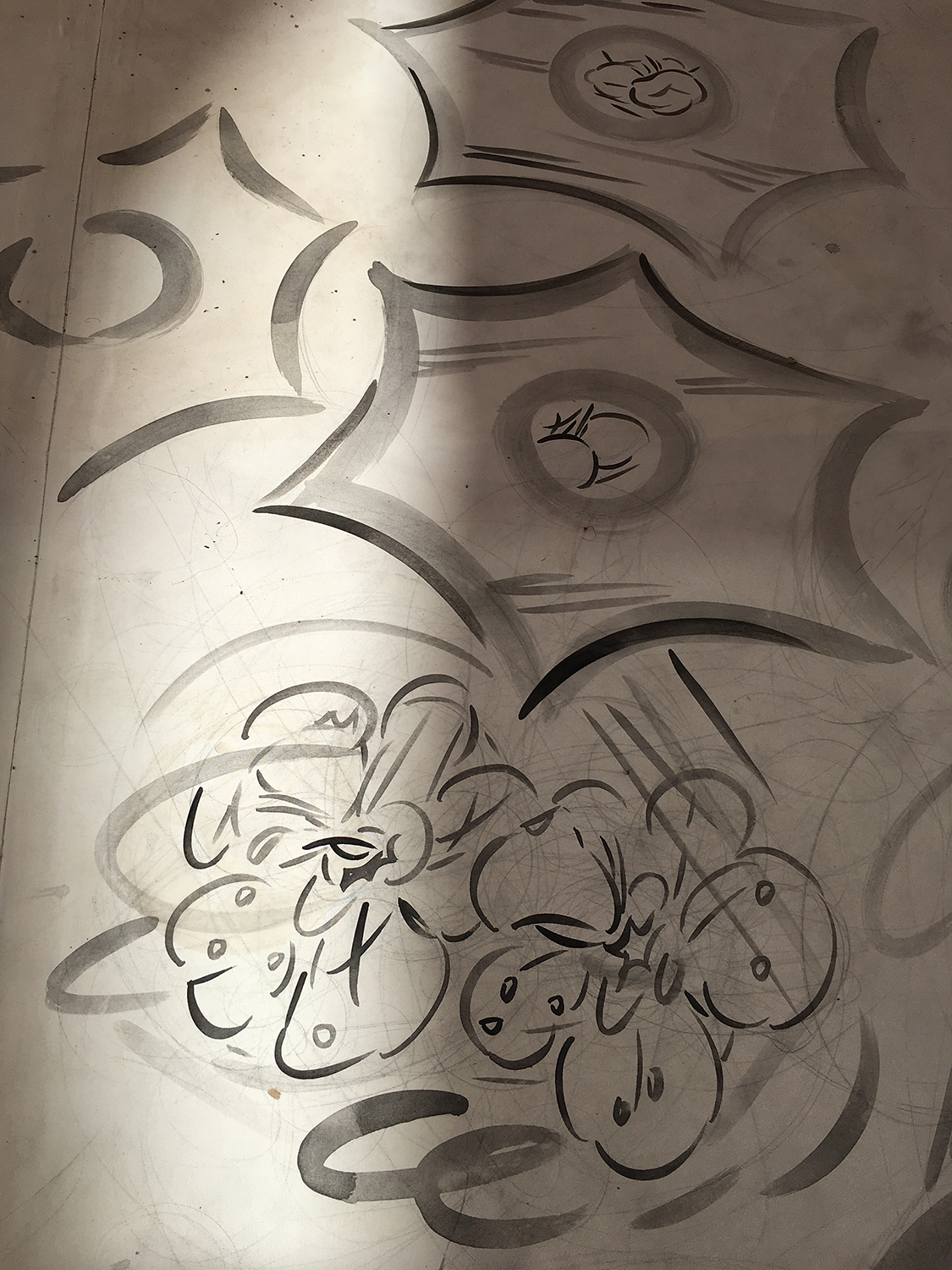

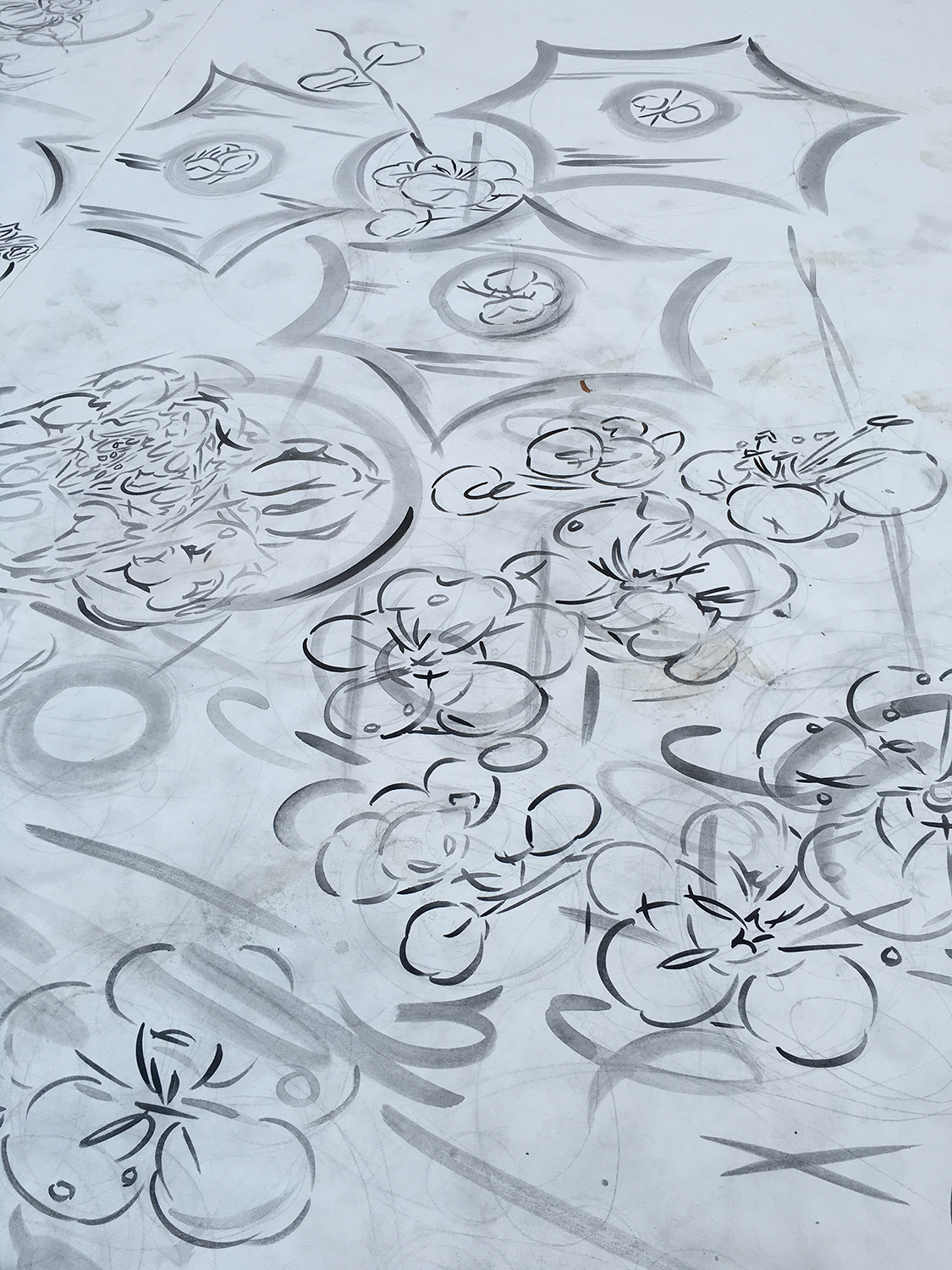

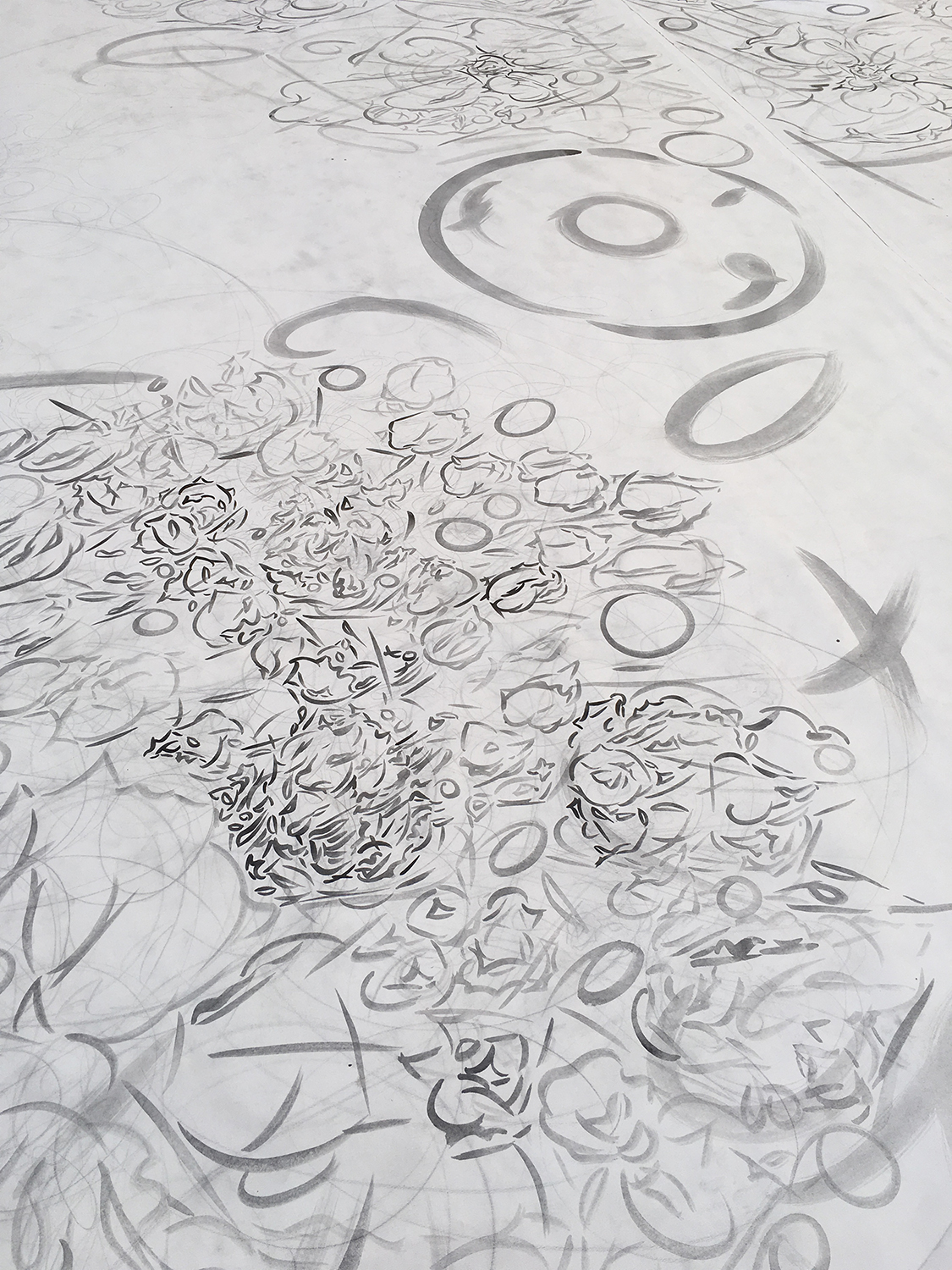

The site-specific floor painting, to be created inside the now empty courtyard of the castle of Vélez Blanco, will be drawn as a performance over a two to three week period. The work becomes a reciprocal cultural gesture from New York to Spain, signaling the next step in an on going conversation about relocation and regeneration.

Executed in plan and seen from above, the castle drawing re-envisions motifs from the patio decoration in an abstract landscape with a rotating horizon. Drawing becomes the activity that grounds the connection between soul and hand in the service of creating a new, ephemeral “skin”. Is it possible to envision a future trajectory for the castle as a regenerative source for new art and ideas, a happy parade of new skins and souls, to create a gathering point and concentration of energy that emanates from this special location? A trajectory that simultaneously celebrates its origin and courts change? An utterly human course, expressed by reliance on the steady work of mark-by-mark accumulation. A wide-open, metaphorical road that reaches inside itself, beneath its surface, its exterior, and exposes an interior leap of faith. A self, both doubled and split.

Wall text from the Metropolitan Museum:

"The castle of Don Pedro Fajardo y Chacón (ca. 1478–1546) stands above the town of Vélez Blanco, near the southeastern coast of Spain. Fajardo, raised in the culture of humanism, was governor of Murcia during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella and assisted in suppressing Moorish rebellions in their lands. By royal act, he was given the town of Vélez Blanco, and between 1506 and 1515 he erected a castle with a central courtyard embellished with Italian Renaissance ornament in local Macael marble craved by craftsmen from Lombardy.

Ornament in this style was known in Spain as "a lo Romano," reflecting its origins in the monuments of Roman antiquity. Designs composed of tiered candelabra and imaginary hybrid creatures such as those surrounding the doors and windows of the patio were disseminated throughout Europe in the prints of Italian artists, themselves inspired by the ancient monuments rediscovered in Rome in the early Renaissance. The patio carvings are among the earliest of this style in Spain and antedate any of these published designs. The coats of arms carved between the arches of the arcade are those of Don Pedro and his second wife, Doña Mencía de la Cueva Mendoza de la Vega y Toledo, a member of the powerful and cultivated Mendoza family, influential advocates of the culture of Renaissance humanism.

The patio's marble fittings were sold by the castle's owner in 1904. George Blumenthal acquired them in Paris in 1913 and had them incorporated in his New York town house. In 1945, after his death and the demolition of his residence, the approximately two thousand marble blocks were brought to the museum, where they were reassembled, as faithfully as possible, in 1964."